La mobylette incarne bien plus qu’un simple moyen de transport : elle représente une période dorée de la mobilité urbaine française, symbole de liberté et d’indépendance pour les générations qui l’ont chevauchée. Aujourd’hui, plusieurs musées en France préservent ce patrimoine vivant en exposant des collections exceptionnelles de cyclomoteurs et de deux-roues historiques. Que vous soyez un passionné de mécanique ou un nostalgique des années 1970-1980, ces temples de la mobylette vous offrent une plongée fascinante dans l’histoire industrielle et culturelle de France. Cet article vous guide à travers les incontournables musées consacrés à la mobylette et aux cyclomoteurs en France, chacun présentant des collections uniques et des histoires émouvantes.

Implanté dans la rue de la Fère à Saint-Quentin, en Picardie, le Musée Motobécane occupe un lieu hautement symbolique : l’ancienne usine qui produisit la première Mobylette française. Ce n’est pas un hasard si ce musée, ouvert en 2012, s’installe précisément sur le site historique où naquit une légende automobile.

Motobécane, fondée en 1923 par Charles Benoit, Abel Bardin et Jules Bézenech, devint rapidement l’un des plus grands fabricants de deux-roues au monde. À partir de 1951, l’usine de Saint-Quentin se concentra exclusivement sur la fabrication de la Mobylette, le modèle qui allait révolutionner la mobilité urbaine française. Entre 1949 et 2002, Motobécane produisit un total impressionnant de 14 millions de Mobylettes.

Le musée expose plus de 120 modèles de la marque aux « deux têtes de gaulois », complétés par plus de 100 machines en réserve, formant un portrait quasi-complet de l’évolution technique de la Mobylette. Parmi les pièces maîtresses figurent les légendaires modèles « Bleue » AV78, symbole du deux-roues français dans les années 1970-1980.

Ce qui distingue particulièrement ce musée, c’est son intégration au sein du Village des Métiers d’Antan, un ensemble muséographique de 3 200 m² reconstitutionnant avec authenticité l’artisanat des décennies passées. Cinquante-cinq ateliers métiers anciens permettent au visiteur de ne pas seulement contempler les machines, mais aussi de comprendre le contexte industriel et social dans lequel la Mobylette s’est développée.

Depuis 2002, lorsque la dernière Mobylette sortit des chaînes de montage de Saint-Quentin, le musée s’est imposé comme le gardien du patrimoine Motobécane, préservant la mémoire d’une marque emblématique qui appartient aujourd’hui à Yamaha (MBK Industrie).

À Riom, en Auvergne, existe un musée d’exception créé par la détermination d’un seul homme: Guy Baster. Son histoire personnelle, intimement liée à sa passion pour les deux-roues depuis l’âge de 13 ans, incarne l’essence même du collectionneur passionné.

Guy Baster découvrit sa première moto à 13 ans : une Motobécane 100 cm³ trouvée dans une vieille grange. Cette rencontre le marqua à jamais. Après son CAP d’horloger, il dépensa sa première paie pour acheter quatre motos, parmi lesquelles une Vincent Grey Flash, une Gnôme Rhone XA avec side-car Bernardet et une Zundapp K800 4-cylindres. Doté d’une volonté remarquable, Baster voyagea en Suisse, Italie, Belgique, Danemark et même aux États-Unis pour enrichir sa collection de machines prestigieuses comme les Indian et Henderson.

C’est en 1992 que Guy Baster, transformant l’atelier de carrosserie de son garage en musée, créa l’un des plus importants espaces dédiés au deux-roues anciens en France. Aujourd’hui, le Musée André Baster rassemble plus de 400 deux-roues provenant de 1905 à 1985 : des motos prestigieuses (Brough Superior SS 100 de 1927, 1000 Vincent, 750 MV AGUSTA), des side-cars légendaires, des cyclomoteurs français et étrangers, des scooters rares. L’une des pièces uniques exposées reste la TRAIN 4-cylindres de 1930, dont un seul modèle a jamais été recencé au monde.

Le musée s’étend sur 2 000 m² d’exposition, complétés en 2000 et 2008 par deux extensions majeures. La deuxième extension, créée en 2008, reconstitue une rue de l’enfance de Baster, avec boutiques d’époque, amplifiant l’atmosphère immersive. Des affiches historiques, des plaques émaillées et un décor d’exception enrichissent l’expérience de visite.

Niché dans le cœur viticole de la Bourgogne, le Château de Savigny-lès-Beaune cache dans ses murs et ses dépendances l’une des plus vastes collections de motos historiques de France, créée par le collectionneur Michel Pont depuis 1979.

Michel Pont, un passionné fervent, ouvrit les portes de son château au public en 1979 pour partager ses obsessions de collectionneur. Depuis cette date, Savigny accueille environ 30 000 visiteurs annuels venus contempler des merveilles roulantes.

La collection de motos s’étend sur 250 machines datant de 1902 à 1960, couvrant toutes les nationalités : Norton, Vincent, Gilera, Velocette, M.V., Rudge, AJS, Terrot, Honda, Blériot, Peugeot, BSA, NSU, Horex, Saroléa. Parmi les pièces maîtresses figurent les motos de Jean Mermoz, l’aviateur légendaire, et celle du Chanoine Kir, dignitaire bourguignon. Chaque machine est présentée dans une scénographie sobre laissant parler les lignes de la carrosserie, la noblesse des aciers et l’ingéniosité mécanique.

Au-delà des motos, le Château de Savigny propose une expérience muséale multifacette : 30 prototypes de voitures de course Abarth, une centaine d’avions de chasse et hélicoptères dans le parc, 8 000 maquettes (dont 1 200 motos au 1/18e), 20 camions de pompiers datant de 1905-1984, et un musée unique en Bourgogne du matériel viticole avec 30 tracteurs-enjambeurs des années 1946-1956.

Entre les plages du Débarquement de Normandie, à Musulmville, existe un musée singulier né de la passion isolée d’un collectionneur : Station 70. Durant plus de 50 ans, Luc Legleuher accumula véhicules, miniatures et objets vintages, créant un véritable hymne à l’époque routière des années 1920-1980.

Le Musée de la RN 13 représente l’aboutissement de cinq décennies de collecte menée par Luc Legleuher, passionné fou de Mobylette et nostalgique des routes de vacances. Ce musée unique, reconnu comme musée officiel de la RN13 par la Fédération Française des Véhicules d’Époque et labellisé au niveau européen, capture l’atmosphère des départs en vacances via la mythique route nationale.

Les collections exposées comptent 70+ véhicules (automobiles, motos, cyclomoteurs, vélos), complétés par une exceptionnelle collection de 10 000 miniatures et 150 plaques publicitaires émaillées datant des années 1920-1980. Luc Legleuher y reconstitua même un garage années 1950 fonctionnel avec bistrot rétro sur place, immergant le visiteur dans l’ambiance des années de gloire routières.

La singularité de Station 70 réside dans son atmosphère conviviale et authentique. En arrivant, c’est dans une ancienne remorque à glace Motta que Luc accueille les visiteurs, établissant immédiatement le ton : ici, pas de muséographie froide, mais une célébration chaleureuse du patrimoine des deux-roues et de l’automobile populaire.

Dans l’Abbaye Royale de Celles-sur-Belle, en Nouvelle-Aquitaine, repose une collection de 45 motos exceptionnelles, réunies par Pierre Certain, mécanicien de métier et passionné de rallye, qui restaura patiemment chaque machine avec expertise.

Pierre Certain consacra sa vie aux deux-roues. Mécanicien de profession, il accumula les connaissances techniques sur des dizaines de modèles différents, inventa ses propres machines de course et devint expert reconnu en matière de mécanique motocycliste. Fou de voyages, il parcouru des dizaines de milliers de kilomètres à travers l’Europe au guidon de ses motos, découvrant et acquérant progressivement les machines qui constitueraient sa collection.

Le musée expose 45 motocyclettes d’exception datant de 1903 aux années 1960, provenant de manufactures prestigieuses : Terrot, BSA, Rudge, Norton, Zundapp, BMW, Nimbus et autres marques historiques anglaises, allemandes, américaines, belges et italiennes. Certaines machines sont restaurées impeccablement, d’autres conservées dans leur « jus » d’origine, offrant aux visiteurs une opportunité rare de contempler des deux-roues centenaires en état de marche.

Ce qui singularise cette collection, c’est qu’elle ne se limite pas à exposer des machines trouvées : Pierre Certain créa lui-même des modèles expérimentaux et ses propres pièces de rechange, témoignant d’une compréhension mécanique profonde. Depuis la cession de sa collection à la mairie de Celles-sur-Belle, elle est devenue un patrimoine communal préservé, géré par l’association Classic Moto Cellois qui organise régulièrement des sorties conviviales pour passionnés.

À Châtellerault, dans le département de la Vienne, existe un musée hors du commun : Le Grand Atelier. Anciennement musée Auto-Moto-Vélo, il occupe depuis 1979 l’enceinte de la Manufacture d’Armes historique (créée en 1819), transformant un site industriel du XIXe siècle en temple de la mobilité.

Le Grand Atelier fut créé grâce à la passion du collectionneur Bernard de Lassée, fondateur de l’Automobile Club de l’Ouest et représentant de la France à la Fédération internationale des véhicules anciens. Après sa mort en 1991, la ville de Châtellerault acquit ses collections et créa le Musée Auto-Moto-Vélo. En 2019, le musée fut réorganisé et rebaptisé Le Grand Atelier, musée d’art et d’industrie.

Sur 3 000 m² de exposition, le musée présente trois parcours distincts : Auto Moto Vélo, la Manufacture d’Armes de Châtellerault, et le Cabaret du Chat Noir parisien. L’espace Auto-Moto-Vélo expose des véhicules du XIXe au XXIe siècles, incluant automobiles, motos, vélos et accessoires historiques.

Ce qui distingue particulièrement Châtellerault, c’est sa remarquable collection de 17 scooters français, collection unique formant quasi la totalité des modèles de scooters français fabriqués dans les années 1950-1960. Parmi les pièces maîtresses figurent le Peugeot S57 (1957), le Mors S1C de 1951 (premier scooter de la Sicvam), et le Peugeot S57 C avec garde-boue avant pivotant. Cette collection, rachetée en 1999 au collectionneur Yves Dumetz, représente un témoignage crucial de l’ingéniosité française dans la mobilité urbaine des Trente Glorieuses.

Après avoir exploré ces musées exceptionnels, une expérience unique vous attend à Paris : une visite guidée originale en Peugeot 103 restaurée, convertie en électrique.

Paris en Mobylette propose plusieurs parcours guidés par un docteur en histoire urbaine de la Sorbonne, combinant passion pour les deux-roues et découverte du patrimoine parisien. Vous pouvez suivre « Les Splendeurs de Paris » (Notre-Dame, Tour Eiffel, Pyramide du Louvre), « Les Secrets de Paris » (quartiers-villages comme Montsouris ou la Butte aux Cailles), ou « Les Lumières de Paris » (monuments illuminés la nuit).

Ces visites offrent l’occasion parfaite de compléter votre compréhension du phénomène Mobylette : après avoir admiré les machines dans les vitrines des musées, venez les redécouvrir sur les pavés authentiques de la Ville Lumière, au cœur de l’histoire urbaine qui forgea sa légende.

La mobylette ne se résume pas à une machine : elle incarne plusieurs générations de culture, de mobilité populaire et d’innovations techniques françaises. Les six musées présentés dans cet article forment un parcours complet à travers l’histoire et l’évolution du cyclomoteur en France.

De la collection quasi-complète des Motobécanes de Saint-Quentin aux machines exceptionnelles du Château de Savigny, des pièces uniques du Musée André Baster à la collection d’expertise de Pierre Certain, chaque musée offre une perspective unique sur ce patrimoine vivant.

Que vous soyez restaurateur passionné, collectionneur nostalgique ou simplement curieux d’histoire industrielle, ces musées consacrés à la mobylette promettent une expérience riche et émouvante. Et pour une immersion complète, ne manquez pas de conclure votre odyssée cyclomotoriste par une balade parisienne en Peugeot 103 restaurée avec Paris en Mobylette.

La mobylette a façonné le paysage urbain français pendant cinquante ans. Ces musées en sont les gardiens vigilants, conservant la mémoire d’une époque révolue mais jamais oubliée.

La mobylette est bien plus qu’un simple moyen de transport : c’est un symbole de liberté, de nostalgie et d’aventure. Pour les passionnés de deux-roues et de cette icône française de la mobilité urbaine, trouver le cadeau parfait relève du défi. Qu’il s’agisse d’un fan de restauration, d’un nostalgique des années 1970 ou d’un amoureux de mécanique vintage, voici cinq idées cadeaux qui raviront tous les adeptes de la mobylette.

Pour tous les fans de mobylette résidant à Paris ou visitant la capitale, rien n’égale l’expérience unique d’une visite guidée aux guidons d’une véritable Peugeot 103 restaurée. Paris en Mobylette propose plusieurs formules permettant de redécouvrir la Ville Lumière sous un angle entièrement nouveau.

Cette expérience conviviale offre l’opportunité de parcourir Paris sans fatigue, loin des embouteillages et des transports en commun surpeuplés. Les mobylettes utilisées sont des Peugeot 103 entièrement restaurées et converties en électrique par des professionnels agréés, combinant ainsi respect du patrimoine et modernité écologique.

La visite est guidée par un docteur en histoire urbaine de la Sorbonne, qui partage son expertise avec passion. Les itinéraires proposés conviennent à tous les goûts :

Le point fort de cette expérience ? Les visiteurs n’ont besoin que d’un simple permis de vélo ou du BSR pour conduire. Une session de prise en main gratuite permet à chacun de se familiariser avec sa monture avant le départ. Possibilité de visite privée (1-6 personnes) à partir de 345€. C’est un cadeau mémorable qui allie passion pour la mobylette et découverte culturelle.

Pour le fan de mobylette qui aime entretenir lui-même sa machine, offrir des outils et équipements de qualité est un cadeau très apprécié. Voici une liste précise d’équipements indispensables avec les gammes de prix :

Outils essentiels :

Équipements pour la mobylette :

L’offre de ces équipements montre au passionné que vous comprenez son amour pour sa machine et vous l’aidez à entretenir son patrimoine avec des outils et accessoires dignes de ce nom.

La Peugeot 103 est une légende sur deux roues, avec une histoire riche couvrant plusieurs décennies. Offrir une belle édition illustrée ou une encyclopédie détaillée sur cette machine mythique plaira à tous les fans de mobylette ayant du goût pour l’histoire et la culture.

Ces publications sont souvent devenues des collector’s items, particulièrement celles publiées directement par les passionnés ou les clubs de mobylettistes. Certains livres se concentrent sur les techniques de restauration, tandis que d’autres explorent la place symbolique de la mobylette dans la société française des années 1970 à 2000. C’est un cadeau sophistiqué qui allie connaissance, nostalgie et respect pour le patrimoine.

Pour un fan de mobylette, l’accessorisation de son engin et l’adoption d’un style vestimentaire adapté font partie intégrante de la passion. Offrez des vêtements et accessoires de qualité aux codes esthétiques de l’époque :

Pour un cadeau original et enrichissant, offrez une visite dans l’un des musées français dédiés à la mobylette et aux deux-roues. Voici une sélection de musées ouverts à travers la France :

La clé pour choisir le cadeau idéal pour un fan de mobylette est de considérer son profil : restaurateur passionné, collectionneur nostalgique, ou aventurier urbain ? Une ballade guidée avec Paris en Mobylette ravira les amateurs de nouvelles expériences, tandis qu’un kit d’équipements et d’outils séduira les bricoleurs. Un livre de référence plaira aux passionnés d’histoire et de mécanique, tandis qu’une visite en musée constituera une sortie mémorable. Quel que soit votre choix, vous offrirez bien plus qu’un simple cadeau : vous célèbrerez une passion, une histoire et l’esprit de liberté que la mobylette incarne depuis plus d’un siècle.

Paris seduces millions of visitors annually with its romantic boulevards, world-class museums, and iconic monuments. Yet beneath the City of Light’s glittering surface lies a darker chapter—one few tourists ever contemplate while sipping coffee at a Parisian café. The dark history of Paris is not merely a footnote in European history; it represents pivotal, often brutal moments that forged modern France. For the discerning traveler seeking authenticity beyond the postcard, understanding these ten bloody events transforms Paris into something far more profound: a living classroom of human experience, both triumphant and tragic.

This comprehensive exploration of Paris’s violent past will challenge your perception of this enchanting city. Whether you’re planning a historical walking tour or deepening your cultural knowledge before arrival, these ten watershed moments reveal how tragedy, persecution, and conflict have repeatedly tested Parisian society—and paradoxically, shaped its resilience.

And if you’d like to visit Paris, accompanied by a historian, while riding a vintage French moped, follow the link below.

When the Black Death swept across medieval Europe in 1347, Paris became an epicenter of both epidemiological catastrophe and religious violence. As thousands died from the mysterious plague, Parisian authorities and mobs, desperate for explanations, found their culprits: the city’s Jewish community.

In a chilling reversal of logic, Jewish residents were accused of poisoning wells to spread the plague—a lie that would echo through centuries of antisemitic persecution. Between 1347 and 1352, hundreds of Parisian Jews were killed in organized pogroms, their homes plundered, their communities destroyed. The accusation was scientifically absurd: the plague ravaged Jewish populations at identical rates as Christian populations. Yet reason proved powerless against fear.

Remarkably, Pope Clement VI issued papal bulls in 1348 defending Jews and urging church leaders to provide sanctuary. His personal physician, Guy de Chauliac, even published medical arguments proving the accusations false. Yet local authorities in Paris and beyond ignored Rome’s appeals. The pogroms persisted until the plague itself waned by 1351, taking with it any lingering interest in targeting the Jewish community.

This dark chapter of Paris’s history illustrates how catastrophe weaponizes prejudice—a pattern that would repeat itself in later centuries.

The early 15th century found Paris torn by the ferocious Armagnac-Burgundy civil war. When the Burgundian faction seized control of the capital in May 1418, their revenge was swift and merciless. Bernard VII d’Armagnac, the powerful military commander of the rival faction, became their primary target.

On June 12, 1418, a mob of Parisian butchers and Burgundian soldiers attacked the Conciergerie prison where Armagnac was held. The scene that followed was savage: Armagnac was beaten, stripped naked, and dragged through the streets for three days before being dumped near a garbage heap in a final act of dehumanization. Beyond Armagnac’s death, thousands of Armagnac supporters were hunted through Paris’s streets, arrested, and murdered—the exact toll remains disputed by historians, but estimates suggest 3,000 to 5,000 deaths.

Visiting Paris’s Conciergerie today, few tourists realize this fortress-prison was once the site of one of medieval Europe’s most brutal political purges. The massacre of 1418 fundamentally altered French politics, ensuring Burgundian dominance and reshaping the trajectory of the Hundred Years’ War.

If Paris’s dark history contains a single event that epitomizes the horror of religious extremism, it is the St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre on August 24, 1572. The massacre began as a targeted assassination—King Charles IX, pressured by the ultra-Catholic Guise family, ordered the killing of Admiral Gaspard de Coligny, the military leader of French Protestants.

The assassination triggered something far worse. On the night of August 23–24, Catholic mobs began systematically hunting Protestants (Huguenots) through Paris. For three consecutive days, the violence spiraled into genocidal rampage. Estimates suggest 7,000 to 10,000 Protestants were slaughtered in Paris alone, with contemporary witnesses describing streets “red with blood” and victims “killed like sheep at slaughter”.

Horrifyingly, the massacre didn’t stop in Paris. As news spread, similar “St. Bartholomew’s” killings erupted in at least twenty provincial cities. Modern historians estimate the total death toll across France reached 10,000 to 15,000 people. Pope Gregory XIII, apparently unbothered by the slaughter of Christians, celebrated with special thanksgiving masses—a response that remains one of history’s most damning commentaries on institutional religious extremism.

The place de la Concorde, where so many later victims would meet their end on the guillotine, became a pilgrimage site for survivors seeking to commemorate fallen relatives. Modern dark history tours often begin at Pont Saint-Michel, where some bodies were thrown into the Seine.

The dark history of Paris during the mid-17th century took a different form: civil disorder rooted not in religious conflict but in political power. The Fronde (meaning “sling” or “catapult” in French—a weapon used by street children) was Paris’s only significant uprising against royal authority before the French Revolution.

In 1648, financial hardship and the arbitrary removal of judges’ guaranteed positions sparked a rebellion led by magistrates of the Paris Parlement (the kingdom’s highest court). What began as a legal dispute escalated into urban warfare. By August 1648, barricades covered Paris’s streets. Magistrates were assassinated, government officials hunted, and the city descended into chaos that lasted until 1653.

While specific death tolls remain imprecise—estimates range from hundreds to thousands—the social disruption was immense. Entire neighborhoods became battlegrounds. The royal family itself was forced to flee, with young King Louis XIV witnessing the fragility of absolute power firsthand. This experience haunted him throughout his reign and motivated his later decision to move the court to Versailles, away from turbulent Paris.

The Fronde challenged a fundamental question: could the common people and magistracy challenge a king’s authority? The answer was yes—a lesson not lost on revolutionaries 140 years later.

Few episodes in European history equal the sheer horror of La Terreur (The Reign of Terror). Between September 1793 and July 1794, Paris became a city of fear, suspicion, and mass execution.

Under the Committee of Public Safety, led by Maximilien de Robespierre, an estimated 16,594 death sentences were carried out across France, with 2,639 occurring in Paris alone. The guillotine, that supposedly humane execution device, became the symbol of revolutionary fanaticism. On the place de la Concorde, the blade fell so frequently that Parisians joked about the “Razor of the National Razor.”

Contrary to popular belief, aristocrats were not the primary victims—they represented less than 10% of the dead. Instead, ordinary Parisians were arrested on suspicion of “counter-revolutionary sentiment,” a charge with no fixed definition. Priests who wouldn’t swear allegiance to the state were executed. Political opponents of Robespierre vanished. Common workers accused of hoarding food met the guillotine. By June and July 1794, executions peaked at truly genocidal rates.

Marie-Antoinette’s execution on October 16, 1793, symbolized revolutionary triumph—yet her death was marked not by celebration but by eerie silence as thousands witnessed the former queen’s severed head displayed. The revolutionary government was executing its own leaders. Robespierre himself, after orchestrating thousands of deaths, was guillotined on July 28, 1794.

Walking through Paris today, most visitors pass the place de la Concorde without grasping the horror that unfolded there. Approximately 1,300 executions occurred in that square alone. Memorial plaques and guided historical tours now help tourists understand this darkest chapter of Paris’s democratic experiment.

The dark history of Paris continued into the modern era with Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte’s coup d’état on December 2, 1851. The president, facing imminent constitutional limits on his power, orchestrated a lightning strike that would reshape France.

In the night of December 1–2, 60,000 troops occupied every strategic point in Paris. Printing presses were seized, cafés closed, and stable yards padlocked to prevent residents from obtaining horses to flee the city. The strategy was methodically totalitarian: eliminate opposition leaders’ ability to organize or escape. Over 27,000 people were arrested in the following days.

Street resistance erupted on December 3–4, when Parisians attempted to build barricades in working-class eastern districts. Government troops responded with overwhelming force. Estimates of deaths range from 400 to 1,000, with some historians placing the figure higher. Soldiers fired on crowds with artillery, and bodies accumulated in Paris’s streets.

What makes this event crucial to Paris’s dark history is its demonstration that even constitutional systems could be dismantled through military occupation. The coup’s success emboldened authoritarian movements across Europe. Yet it also galvanized republican resistance—many of those arrested would become the founding generation of the Third Republic, France’s longest-lasting democratic system.

The year 1832 brought tragedy upon Paris in the form of a cholera epidemic that killed 18,402 people. In the poorest neighborhoods, mortality rates approached apocalyptic levels. Desperate and suspicious, Parisians seized on a dangerous rumor: the government had poisoned wells to reduce the population.

This paranoia erupted into violence following the funeral of Jean Maximilien Lamarque, a beloved military general and monarchy critic who had fallen victim to cholera. His funeral procession of 100,000 mourners transformed into a political demonstration. When a scarlet flag reading “Liberty or Death” was raised, shots rang out.

Over the next two days, republicans constructed barricades around the city, particularly in the Latin Quarter near the church of Cloître Saint-Merri. Government forces, numbering 60,000 troops, surrounded the rebels. The resulting clash claimed approximately 800 lives, with 93 insurgents and 73 soldiers killed.

The June Rebellion would later inspire Victor Hugo’s masterpiece “Les Misérables,” immortalizing the idealism and tragedy of those who died fighting for political change. For modern tourists exploring Paris, the narrow streets of the Fifth Arrondissement still echo with this history.

The dark history of Paris reaches one of its most visually apocalyptic moments during the Semaine Sanglante (Bloody Week) of May 21–28, 1871. The Paris Commune, a short-lived radical government established in the chaos following the Franco-Prussian War, had attempted to create a workers’ paradise. The French national government had other ideas.

When government troops entered the city on May 21, they encountered not a disorganized mob but a structured military force of Commune defenders. What followed was a week of urban warfare of breathtaking brutality. Communards set fires throughout the city—the Tuileries Palace, the Hôtel de Ville, the Palais de Justice all burned.

Between 10,000 and 20,000 Communards were killed—some in combat, many summarily executed after capture. Soldiers showed little mercy, as their officers viewed the Commune not as a political movement but as a revolutionary threat to civilization itself. The massacres continued even after organized resistance collapsed.

In their final acts of defiance, Commune leaders executed roughly 100 hostages, including Georges Darboy, the Archbishop of Paris. This gave government forces justification for intensified reprisals—though the disproportionality of the response (10,000 Communards killed versus 100 hostages executed) reveals the government’s intent to exterminate the movement entirely, not simply restore order.

Many Paris neighborhoods still bear the scars of the Bloody Week. The walls and buildings of the eleventh arrondissement, where the Commune’s last barricades stood, contain embedded bullets from 1871. Several guided historical tours now focus specifically on this episode.

The dark history of Paris reaches its most devastating chapter during World War II with the Vel’ d’Hiv roundup—the largest mass arrest of Jews in Western Europe. On July 16–17, 1942, French police, acting under the Vichy regime and Nazi occupation, conducted raids across Paris and suburbs.

In a meticulously planned operation, approximately 13,152 Jews—including 4,115 children—were arrested. Families were torn apart in dawn raids. Many were barely given time to dress before being herded into buses and trucks.

The primary detention point was the Vélodrome d’Hiver (Winter Velodrome), a sports arena in the 15th arrondissement. Nearly 8,000 people were crammed into this building with almost no provisions—no food, no water, no sanitation facilities. Children separated from parents were housed in different sections, a cruelty designed to facilitate later deportations.

After five days in these nightmarish conditions, detainees were transported in cattle cars to camps in the Loire Valley, then onward to Auschwitz. Of the 13,152 arrested, fewer than 100 adults survived the war.

For decades, France maintained an official conspiracy of silence around the Vel’ d’Hiv. The government, ashamed of French collaboration, downplayed the round-up’s significance. It wasn’t until 1995 that President Jacques Chirac formally acknowledged France’s responsibility. In 2017, the Mémorial de la Shoah (Holocaust Memorial) opened on the site of the old velodrome, finally giving voice to the victims.

The Vel’ d’Hiv story fundamentally challenges the myth of France as a beacon of freedom. It reveals how institutions, individuals, and an entire society can become complicit in genocide. Educational historical tours now include this site as essential context for understanding both Paris and the Holocaust.

The final and most recently acknowledged episode in Paris’s dark history occurred on October 17, 1961—a massacre so systematically covered up that it remained official history’s forgotten crime for nearly four decades.

As the Algerian War of Independence neared conclusion, Paris’s Algerian population—numbering in the hundreds of thousands—faced systematic discrimination. On October 5, 1961, Police Prefect Maurice Papon announced a discriminatory curfew: all Algerians were forbidden from leaving their homes between 8:00 PM and 5:30 AM.

In response, the National Liberation Front (FLN) organized a peaceful march for October 17. Between 20,000 and 40,000 Algerians, many families with children, peacefully demonstrated in Paris’s streets. They carried no weapons; demonstrators were searched before boarding buses and metro cars.

The police response was immediate and savage. Nearly 2,000 officers, supported by riot police and auxiliary forces, systematically attacked the demonstrators. Police fired weapons into crowds. Protesters were beaten with cudgels. Most horrifically, dozens were thrown into the Seine River, where they drowned.

The official death toll announced by authorities: three. Historians now concur that at least 100 people were killed on the night of October 17 alone, with total casualties ranging from 200 to 300. Bodies washed up on the Seine’s banks for weeks afterward.

Over 12,000 Algerians were arrested. Many were transported to detention camps and later deported to Algeria. The brutality extended beyond the streets into detention centers, where police continued beating arrested demonstrators.

For 37 years, France officially denied the massacre’s severity. It wasn’t until 1998 that authorities finally acknowledged deaths beyond the fabricated figure of three. President Jacques Chirac placed a memorial plaque on Pont Saint-Michel in 2001. Only in 2021 did President Emmanuel Macron call the massacre “inexcusable”.

The dark history of Paris is not peripheral to understanding this magnificent city—it is central to it. From medieval pogroms to colonial massacres, from religious warfare to revolutionary terror, Paris has repeatedly witnessed humanity at its worst.

The city’s beauty is not diminished by this knowledge—if anything, it deepens. Paris rebuilt itself countless times from ruins. It created unprecedented art and philosophy from suffering. It eventually faced its own darkness with partial honesty.

That resilience, forged through violence and acknowledged through memorial, makes Paris not merely a beautiful destination but a profound one.

And if you’d like to visit Paris, accompanied by a historian, while riding a vintage French moped, follow the link below.

A travers cet article consacré à l’usine Motobécane à Pantin, offrez-vous une visite guidée à travers l’histoire industrielle Ile-de-France.

La création de Motobécane en 1923 s’inscrit dans un contexte d’industrialisation dynamique de la région parisienne. Cette entreprise est fondée le 11 décembre 1923 par trois ingénieurs originaires de la S.I.C.A.M. (Société Industrielle de Construction d’Automobiles et de Moteurs), établie elle-même à Pantin : Charles Benoît, ingénieur, Abel Bardin, technico-commercial, et Jules Bénézech, également ingénieur. Selon le récit transmis par la famille, Jules Bénézech, né en 1891 dans le Tarn et formé à l’Institut Électrotechnique de Grenoble, s’était lié d’amitié avec Charles Benoît durant leurs études, l’aidant notamment sur les mathématiques. Après la Première Guerre mondiale—au cours de laquelle Jules servait dans les transmissions tandis que Charles se trouvait aux États-Unis—ils se retrouvent en 1922 à Paris, où Charles travaille déjà à la SICAM aux côtés d’Abel Bardin.

Leur première création, la MB1, motocyclette équipée d’un moteur deux-temps monocylindre de 175 cm³ à transmission par courroie, s’installe d’emblée au 13 rue Beaurepaire à Pantin. Cet emplacement stratégique demeurera le siège historique de la marque. Les trois associés n’avaient pas encore le poids nécessaire pour se lancer dans l’automobile, déjà très présente sur le marché français. « Ils ont eu l’intelligence d’équiper un maximum de personnes en deux-roues », synthétisait Éric Bénézech, petit-fils de Jules, une stratégie de démocratisation de la mobilité qui allait définir la marque pour les décennies à venir.

Le succès commercial s’avère immédiat et dépasse toutes les attentes. Entre 1924 et 1929, plus de 150 000 exemplaires de la MB1 sont vendus, un chiffre impressionnant pour l’époque. Face à cette croissance exponentielle, l’entreprise s’étend progressivement sur l’îlot de la rue Beaurepaire, couvrant bientôt 8 500 m² de terrains. Cette expansion précoce témoigne de la solidité du modèle économique.

En 1926, pour ne pas compromettre le succès de Motobécane en cas d’échec commercial, la maison-mère crée Motoconfort, marque destinée à commercialiser des motocyclettes de plus forte cylindrée et à offrir un double réseau de distribution. Cette stratégie de diversification marque le développement structuré de l’entreprise dans les années 1930.

Parallèlement, en 1925, Jules Bénézech s’associe à M. Pérouse pour créer la société Novi, satellite de Motobécane consacré à la fabrication des équipements électriques pour les cycles. Dans les années 1930, Novi met au point des machines-outils plus performantes permettant de concevoir des moteurs quatre-temps pour les motos Motobécane, mettant fin à la dépendance vis-à-vis des importations de moteurs d’Angleterre. Cette intégration verticale de la production constitue un atout concurrentiel majeur.

L’Ère de la Mobylette : Révolution et Explosion de la Demande

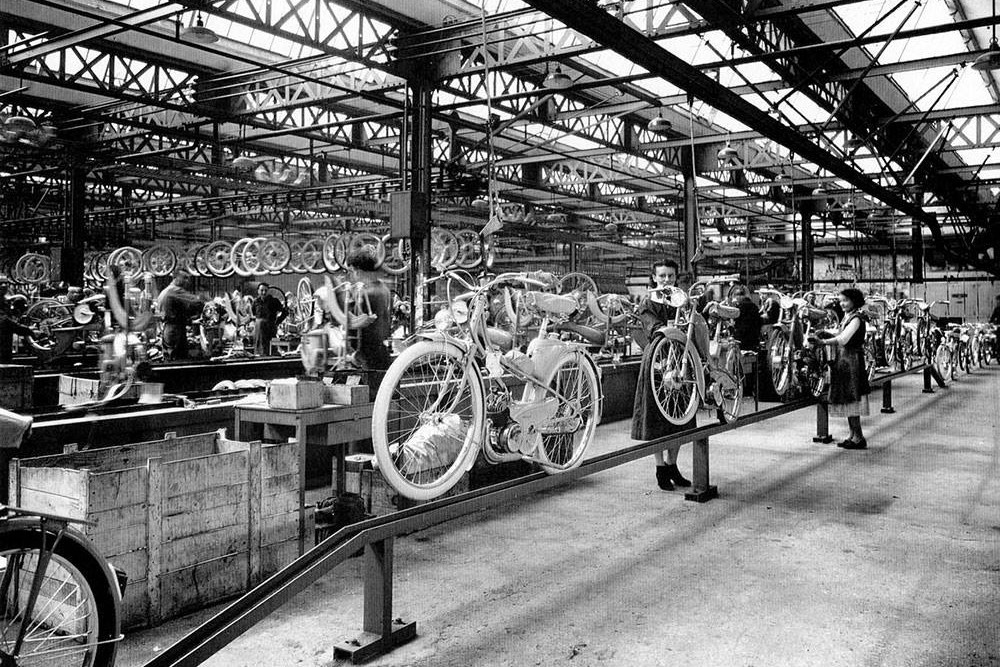

Après la Seconde Guerre mondiale, Motobécane franchit une étape décisive. En 1949, Charles Benoît et l’ingénieur Éric Jaulmes conçoivent la Mobylette, contraction de « mobile » et « bicyclette »—un cyclomoteur révolutionnaire qui capture parfaitement les besoins d’une nation en reconstruction. Économique, fiable et accessible, la Mobylette correspond à la mobilité quotidienne recherchée par des millions de Français. Le succès dépasse toutes les prévisions : dès 1955, le millionième exemplaire sort des chaînes de montage, un jalon extraordinaire en seulement six ans de production.

Entre 1949 et 2002, quatorze millions de Mobylettes seront produites entre Pantin, Bobigny et Saint-Quentin—une production massive qui place Motobécane au cœur de l’histoire économique française de l’après-guerre. À l’apogée, en 1963, Motobécane occupe le premier rang français et européen des fabricants de cyclomoteurs avec une production annuelle de 1 117 769 exemplaires.

Pour faire face à la demande croissante du marché, Motobécane ouvre en 1951 une nouvelle usine entièrement dédiée à la Mobylette à Saint-Quentin, en Picardie. Cette délocalisation reflète l’une des plus grandes vagues d’industrialisation française du XXe siècle. En 1959, un nouvel espace disponible à Saint-Quentin s’avérant insuffisant, l’entreprise érige une usine ultramoderne à Rouvroy sur un champ de betteraves, avec l’aide technique de Renault.

Parallèlement, à Pantin, de nouveaux ateliers et magasins se multiplient stratégiquement : avenue Jean-Lolive pour la fabrication des cycles, avenue Edouard-Vaillant pour les garages, rue Méhul pour la peinture, rue des Vignes pour les chaînes de montage. Le groupe Motobécane, incluant ses filiales La Polymécanique (moteurs) et Novi (matériel électrique), occupe désormais 80 000 m² de terrains sur le territoire et emploie près de 3 000 personnes dans la région parisienne.

Au plus fort de l’activité, le site de Saint-Quentin lui seul accueillait près de 5 000 salariés. Fernand Macaigne, ancien mécanicien cycles ayant débuté à Saint-Quentin en 1960, se souvient d’une atmosphère de fierté collective : « J’ai commencé dans ce grand bâtiment de la rue de La Fère en 1960 comme mécanicien cycles… Je venais travailler à pied, de l’autre côté de Saint-Quentin, et j’étais heureux car tout le monde était bien, c’était familial ».

Cependant, à partir des années 1960-1970, la configuration de l’usine pantinoise change. Le site de la rue Beaurepaire se recentre progressivement sur les activités de stockage, de recherche et d’essais, puis sur les fonctions administratives abritant le siège social. La production elle-même migre vers les sites picards mieux équipés.

Sur le plan technique, la gamme Mobylette s’enrichit considérablement. L’AV78, apparue en 1956 avec son cadre en tôle emboutie et son réservoir de près de 5 litres, marque le début de la lignée mythique des « bleues ». Bien que le premier modèle soit teint en beige, c’est en mars 1957 que l’iconique couleur bleue arrive—d’abord en bleu clair, inspirée par la couleur des voitures de course françaises, mais dans une teinte plus pâle, distincte de celle des bolides. L’AV88, arrivée en 1960, deviendra le modèle le plus connu et le plus durable de la gamme, bénéficiant d’une fourche télescopique classique remplaçant le système d’Earles plus complexe.

Le lancement de la 51 en 1978, dotée du moteur révolutionnaire AV10 à clapets, redonne un élan sportif à la marque, tandis que la Magnum inaugurée en 1987 intègre un moteur à refroidissement liquide—une première pour Motobécane. Des versions « chopper » aux aspirations US émergent dans les années 1990 : West, New West, Copper Black, White Horse et la Daytona Cruiser avec ses jantes à 60 rayons (aujourd’hui très recherchées par les collectionneurs).

La décennie 1970 marque le début du déclin. À partir de 1975, Motobécane subit une baisse continue de ses ventes face à la concurrence étrangère, notamment japonaise (Yamaha, Honda), et à la transformation des modes de transport. Le choc pétrolier de 1973 accélère la crise, les scooters comme le Peugeot 103 s’avérant plus attrayants pour les consommateurs. Malgré les efforts de diversification—la marque rachète même Solex et importe Moto Guzzi en France—l’entreprise historique n’y résiste pas. Elle dépose le bilan en 1983.

Yamaha acquiert l’entreprise en 1983-1984, reformant la marque sous le nom de MBK Industrie. Entre 1987 et 1988, tous les établissements de la région parisienne sont fermés, et les activités sont regroupées à Saint-Quentin puis à Rouvroy, concentrant la production et marquant la fin d’une époque.

L’usine pantinoise de la rue Beaurepaire, berceau de cette aventure industrielle, devient un patrimoine démoli ou converti. En 1988, la Ville de Pantin préempte le site afin d’éviter la spéculation foncière. Un Centre International de l’Automobile y est établi en 1989, qui ferme en 2002. Le groupe Hermès acquiert finalement le site et y installe ses ateliers de manufacture haut de gamme.

Les vestiges architecturaux de la rue Beaurepaire, datant des années 1926-1927, subsistent partiellement comme témoins de cette époque révolue. Depuis 2012, le Musée Motobécane de Saint-Quentin, hébergé dans l’une des anciennes usines à la rue de la Fère, expose plus de 120 modèles de deux-roues, dont des prototypes exceptionnels comme une Mobylette électrique de 1972. Chaque année, environ 20 000 visiteurs, venus de France et d’Europe, foulent les allées du musée pour se replonger dans cette histoire de mobilité populaire.

Bien que Motobécane ait disparu en tant qu’entité indépendante, la passion pour la marque ne s’est jamais éteinte. Des collectionneurs comme Jean-Pierre Ono-dit-Bio, près de Rouen, conservent et restaurent une vingtaine de pièces rares et inédites, incluant des modèles exceptionnels comme la seule survivante des dix exemplaires proposés à la Police Nationale en 1976. En 2007, Jean-Pierre fonde le club Motobécane Passion et crée un site gratuit avec plans et tutoriels ; en 2009, il s’associe à un ami manufacturier pour produire et vendre les pièces en caoutchouc qui ne sont plus fabriquées en usine, permettant la restauration continue d’anciens modèles.

Sur le site de Rouvroy, MBK Industrie, toujours en activité, emploie 625 salariés (hors intérimaires) et produit annuellement 80 000 deux-roues. En 2023, l’entreprise lance un nouveau tournant stratégique : la fabrication de batteries pour vélos électriques, avec un objectif de 60 000 unités annuelles et un investissement de 4 millions d’euros, associé au recrutement de 50 personnes supplémentaires.

Entre 1949 et 2002, quatorze millions de Mobylettes auront été produites, témoignant de l’importance de Motobécane dans l’histoire économique et culturelle française, et de son rôle pivot dans la mobilité de l’après-guerre. La marque reste profondément ancrée dans la mémoire collective, incarnant la liberté d’une génération et la démocratisation de la mobilité urbaine et rurale en France.

Pour les passionnés d’histoire industrielle en Île-de-France, plusieurs lieux patrimoniaux demeurent accessibles :

– Rue Beaurepaire à Pantin : Le site est désormais occupé par les ateliers Hermès. Néanmoins, les vestiges architecturaux datant de 1926-1927 subsistent partiellement, témoins de l’époque de la manufacture originelle.

– Musée Motobécane de Saint-Quentin : Bien qu’en Picardie, ce musée expose l’héritage complet de la marque.

The 1832 cholera epidemic in Paris arrived like an unwelcome ghost—sudden, terrifying, and impossible to ignore. Between March 26 and September 30, 1832, this mysterious disease devastated the French capital, claiming 18,402 lives and exposing deep fractures in Parisian society. Today, this epidemic remains one of the most dramatic chapters in Paris history, revealing truths about poverty, class conflict, and urban desperation that still resonate.

For people interested in Paris’s hidden history, this epidemic tells a story far darker than any Gothic novel—one where science failed, fear bred violence, and the city’s poorest residents paid an unimaginable price.

And if you’d like to visit Paris, accompanied by a historian, while riding a vintage French moped, follow the link below.

Understanding how the 1832 cholera epidemic in Paris occurred requires looking beyond the city. The disease originated in the Ganges Delta in India, where it had been endemic for centuries. In the early 1800s, a new global trade network spread it. Russian armies fighting Persians and Turks carried it westward. By 1830, cholera reached Eastern Europe.

From England (where it arrived in December 1831), the disease crossed the Channel. French ports received infected travelers. By mid-March 1832, cases appeared in Calais.

The 1832 cholera epidemic in Paris began quietly but escalated with horrifying speed. In March 1832, cases first appeared in the northern French port of Calais. By March 26, the disease had reached Paris itself. What followed was unprecedented: the city hadn’t experienced a major plague in over a century, and neither doctors nor officials knew what they were facing. The Vibrio cholerae bacterium wasn’t isolated until 1883. Competing theories blamed bad air (miasma theory), the night air, or poor morals. Some physicians prescribed saline enemas, bloodletting, or strange concoctions. None worked.

The mystery deepened the terror. On April 10 alone, 848 Parisians died in a single day—a figure almost incomprehensible to modern observers. Within the first month of April alone, 12,733 people perished. The speed was apocalyptic: victims developed symptoms in the morning and died by evening, their bodies turning a distinctive blue-gray color before death.

Writer Heinrich Heine, witnessing the chaos firsthand, captured the horror in a letter to German newspapers. He described an Arlequin at a mid-Lent carnival ball who “felt too much coldness in his legs, removed his mask and revealed to everyone’s astonishment a face of violet blue.” The image was both grotesque and prophetic. This blue discoloration gave birth to the French term “la peur bleue” (the blue fear)—an expression that entered the language to describe sheer terror itself.

The 1832 cholera epidemic in Paris had a cruel face: it disproportionately killed the poor. The disease ravaged working-class neighborhoods while sparing the wealthy. In the Saint-Merri district near City Hall, 5.3% of the entire population died. A single street, Rue de la Mortellerie, lost 304 of its 4,688 residents—a devastating 6.4% mortality rate in weeks.

Why? Paris in 1832 was a city drowning in its own filth. The population had exploded from 524,000 in 1789 to 866,000 by 1832, yet the medieval streets remained unchanged. Tenements in the city’s oldest quarters packed 150,000 people per square kilometer into crumbling buildings. Open sewers ran through streets. Drinking water came from contaminated wells. Cholera, transmitted through fecal-contaminated water, found perfect breeding grounds in these conditions.

The working poor lived in squalor. Cordonniers (shoemakers), rag pickers (chiffonniers), water carriers, and laborers inhabited the most pestilent neighborhoods. These were not just the victims of 1832 cholera epidemic in Paris—they were the marked for death by the geography of poverty itself.

Here’s where the 1832 cholera epidemic in Paris takes a darkly human turn. Desperate to understand why the disease was killing their neighbors, many Parisians embraced a terrifying belief: the government and wealthy bourgeoisie were deliberately poisoning them to eliminate the poor.

The panic began with rumors. Then, on April 2, 1832, the Paris police prefect released a circular that backfired catastrophically. Warning of “miserable persons” spreading poison in cabarets and at butcher stalls, the government inadvertently confirmed popular suspicions. Rather than calming fears, the circular inflamed them.

Between April 4 and 5, 1832, angry mobs hunted innocent people accused of being poisoners. A man carrying a bottle? Poisoner. A stranger asking for water? Poisoner. In shocking episodes described by historian Karine Salomé and witnessed by Heinrich Heine, at least six people were beaten to death by crowds convinced they were assassins spreading death. Victims had their bodies dragged through streets or thrown into the Seine.

One victim, Gabriel Gautier, was beaten so severely that witnesses described his body being left for dogs to devour. The brutality was extreme yet comprehensible: terrified people sought targets for their rage. The wealthy had fled the city with physicians and medicine. The poor faced death alone, and they lashed out.

The 1832 cholera epidemic in Paris exposed the city’s vulnerability like nothing else could. The volume of death overwhelmed all systems. Coffin makers ran out of wood. The city couldn’t transport bodies fast enough. Officials tried using artillery wagons to carry corpses, but the noise and rattling broke open caskets, spilling decomposing bodies onto Paris streets. Eventually, they used furniture delivery carts—an image that haunted contemporaries.

These “omnibuses of the dead,” as one witness called them, rolled through empty streets daily. The wealthy fled. A contemporary account noted that horse-rented carriages increased by 500 per day as wealthy Parisians purchased tickets to escape. The opera’s performance of “Robert le Diable” on April 6 was postponed because no one would buy tickets. Paris became a ghost town inhabited by the sick and dying.

The 1832 cholera epidemic in Paris also sparked violent social upheaval beyond the massacres. Garbage workers (chiffonniers) and rag pickers revolted when the government suspended their work. On the same days the cholera massacres occurred, barricades rose in streets. Prisoners at Sainte-Pélagie prison mutinied. The epidemic didn’t just kill—it destabilized the entire social order.

The 1832 cholera epidemic in Paris lasted only seven months, but its impact reshaped the city forever. By killing 18,402 people, it forced France to confront urban decay, poverty, and public health. The government could no longer ignore the filth, overcrowding, and disease festering in working-class neighborhoods.

In response, Prefect Rambuteau (1833-1848) committed to his famous promise: to give Parisians “water, air, and shade.” He built fountains, paved streets, and began drainage projects. These reforms, vastly expanded under Prefect Haussmann (1853-1870), transformed Paris into the modern city we recognize today. The grand boulevards, the sewage systems, the public parks—all were direct responses to lessons learned during the cholera epidemic.

The 1849 epidemic, which killed 19,184 Parisians, further demonstrated that urban hygiene prevented disease. Areas rebuilt after the first epidemic had lower mortality rates. This scientific proof drove policy: in 1850, France passed its first housing sanitation law. The 1832 cholera epidemic in Paris thus became the catalyst for modern urban planning and public health regulation.

For visitors interested in the 1832 cholera epidemic in Paris, several locations matter historically. The Saint-Merri neighborhood, east of the Marais, was one of the hardest-hit districts. The Île de la Cité, crowded and fetid, saw horrific mortality rates. The Hôtel-Dieu hospital, where thousands died, still stands on the island, though rebuilt.

Heinrich Heine witnessed the carnival ball at a venue in central Paris; the scene he described—the masked Arlequin collapsing with a violet face—happened in what’s now the Marais district. Many guided historical tours of Paris now include this epidemic as part of understanding the city’s 19th-century transformation.

The Catacombs and the Cemetery of Montmartre also hold stories of this period. While the cholera dead weren’t buried in the Catacombs (as sometimes claimed in tourist lore), these locations are intrinsically linked to the public health reforms that followed the epidemic.

And if you want to discover Paris, riding a vintage French moped, accompanied by a historian, follow the link below.